Benjamin Franklin was a man who wore

many hats and contributed to the science of electricity and

invention. For historians, he is a complex character who rose from

obscure poverty to be among the great thinkers of the founding of a

new nation. An artisan, he was a self-made man with little formal

education and rose from poverty to wealth. Ordinary citizens

identified with him because he was more in tune with common society

than the other founding gentlemen, like Washington and Jefferson.

George Washington was but a noble British officer, made a Republican by circumstances.

At

the same time, he was a worldly, cosmopolitan European who mingled

easily with lords and aristocrats in Britain and Europe as easily as

the folks at the neighborhood pub. He spent the last 33 years of his

life in Britain and France and people wondered if would ever return

to the nation he had helped establish.

In

the beginning of the falling out between the British Empire and the

American colonies, no one could have predicted he would become one of

the leaders of the American Revolution. Indeed, the revolution,

started with a document entitled the Declaration of Independence,

with apprehension from much of the leadership and representatives of

the colonies. In 1760, Benjamin Franklin was dedicated to the British

Empire as a whole. Those that remained loyal to the monarchy of

England, England itself were called Tories (loyalists).

One would have thought before that declaration that Franklin was a

dedicated Tory.

Another

difference about Franklin was that, like the last civilian governor

of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson,

he had a deep empathy against religious zealots. In 1754, Franklin

and Hutchinson they had worked on the Albany Plan of Union

which would promote intercolonial cooperation and aid in imperial

defense of England. Both were believers that a few reasonable men

should be running state affairs, and regarded the general public with

amusement and disgust if they rioted.

Many

are unaware that Franklin was not a young man and was 70 years old in

1776, the oldest of the revolutionary leadership. He was born of a

different generation than his partners. He had already become famous

from his publishing, discoveries and inventions and was a member of

the Royal Society receiving honorary degrees from universities in the

colonies and Britain, which included the prestigious St .Andrews

and Oxford.

Men of science and philosophers in Europe, consulted him over a

myriad of subjects. As Gordon Wood

wrote, too many take for granted Franklin's patriotism in the

Revolution. He was a man of calculated restraint when it came to

making decisions. What made him decide to join the Republican

revolutionists?

Franklin

wrote an Autobiography that scholars interpret and reinterpret, but

cannot agree as to why he wrote it. It is a transition of an awkward

teenage printer who arrived in Philadelphia to the man he had come to

be known to the world. In his writings, he always inserted his wit

and humor, constantly portraying his self-awareness and his many

interests. He wrote under different persona: Silence Dogood,

Alice Addertongue,

Cecilia Shortface,

Anthony Afterwit,

and, of course, the almanac maker – Poor Richard.

All of his varied personae has made scholars to believe that -

... no other 18th century writer has so many different personae or as many different voices as Franklin. No wonder we have difficulty figuring out who this remarkable man is.[The Canon of Benjamin Franklin: New Attributions and Reconsiderations, J.A.Leo Lemay, University of Delaware Press, 1986; p. 135]

Writing

as Poor

Richard,

he stated:

We shall resolve to be what we would seem. … Let all Men know thee, but no man know thee thoroughly: Men freely ford that see the shallows.

Franklin

was the extreme opposite of John

Adams,

keeping his intentions and feelings to himself. Poor

Richard

wrote:

Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead.

D.H. Lawrence

noted in the 1920s for his vicious attacks (and thus literary enemies) against all of the

Founders, did not spare Franklin. He became more than a man, but a

symbol and too many “historians” have attempted to destroy the

character of the Founders, rather than weed through the legends that

have come to surround them.

Franklin's

life story from poverty to wealth is a remarkable story in itself,

but in the history of the United States not unique for the “promised

land” where immigrants disembarked with only change in their pocket

had seen success through opportunity because of their vision and

intellect.

If

one reads the Franklin Autobiography,

one can see that he made it through the hierarchy of society with

help of influential men.

Franklin's

brother-in-law was a ship captain who sailed a commercial sloop

between Massachusetts and Delaware and learned that Franklin was in

Phil, working in a printshop, and wrote to Ben to persuade the young

runaway to return to Boston. The brother-in-law showed Franklin's

letter of reply to William Keith,

governor of Pennsylvania, who was amazed at the well-written letter

by a 17-year-old and invited Franklin for a drink in a local tavern,

where he offered him the opportunity to become an independent printer

if his father would supply the capital.

In

1774, returned from Boston, where Benjamin had failed to get money

from his father, he stopped in New York with a trunkful of books he

had brought from Boston. Noticed by the colonial New York governor,

William Burnet,

who asked to meet the man with so many books to talk about authors

and books.

Pennsylvanians

were quick to see Franklin's genius. Thomas Denham,

William Allen,

Andrew Hamilton,

and others supported him by lending money, inviting him to their

homes, introducing him to others, and developed a social circle that

benefited the young Benjamin. He recalled later:

...these friends were … of great use to me as I occasionally was to some of them.

As

time passed, he became more than just a wealthy printer and delved

into partnerships and shares in several printing businesses in the

colonies. He established about 18 paper mills during the course of

his business ventures; and it is estimated he was the largest paper

dealer in the colonies and probably Europe. He owned rental property

in Philadelphia and several coastal towns. He was a creditor,

more like a banker, with a great deal of currency loaned out, loans

from two shillings to 200 pounds. Throughout his life he was

involved in land speculation.

In

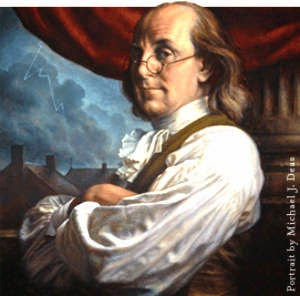

1748, at the age of 42, Franklin believed he had gained enough wealth

and decided to retire from active business. He could then be a

gentleman of leisure who no longer had to work for a living. It was a

major event and he took it serious enough to have a portrait painted

by Robert Feke.

He moved to a more spacious residence and bought several slaves and

left his printing office and shop on Market Street, where his new

partner, David Hall, moved in to run the firm. Most artisans worked

where they lived.

Franklin

was now a gentleman and decided to write and engage in Philosophical Studies and Amusements.

He became a member of the Philadelphia City Council in 1748, being

brought into government and was appointed a justice of the peace in

1749. In 1751 he became a city alderman and was elected from

Philadelphia to be one of the 26 in the Pennsylvania Assembly that

was primarily Quakers. He had grown to be interested in politics and

government, and saw public service as his obligation as a gentleman. He probably got along with the Quakers so well because of his family background was religious, indeed, his father envisioned him to be a minister of the Calvinist denomination. However, Franklin would come to despise religious zealots, who had no room in their life for the wonders of science and discovery; partly, his change in views upon religion was because of his discovery of life among the "lower" class, even prostitutes when he made his first trip to England. But Franklin was not an atheist or could be considered apathetic to the ideas and doctrine of religions.

In

1749, he wrote a pamphlet entitled Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pennsylvania,

an encouragement for education and advancement of young men. Between

the 1750s and early 1760s, one would never imagine that Franklin

would become a revolutionary patriot. He was frustrated with the

“petty disputes” between the colonial assemblies and colonial

governors. In 1757, he went to England as the agent of the

Pennsylvania Assembly in order to persuade the Crown to remove the

Penn family as proprietors of Pennsylvania and make Pennsylvania a

royal province. Rumors were that he intended to become the first

royal governor of Pennsylvania.

Franklin's

good sense and confidence amazed high level individuals in the

British government, amazing his English friends. In Franklin's

Philadelphia home, he proudly displayed a picture of the chief

minister to King George III,

Lord Bute,

and bragged of being acquainted to him. He stated that no one brought

up in England could ever be happy in America. He claimed that America

was corrupt and not England. Franklin had become absorbed into the

English society and mentioned frequently of staying in England. But

he had to return in 1762 because he had obligations in his post

office business; but vowed to return to England.

As

you can see, in the early 1760s, Franklin was a loyalist, a royal

supporter – a Tory.

In

1764, Franklin was back in England, just in time for the Christmas

fanfare, where his involvement in the Stamp Act the following year

revealed how much he misunderstood popular government and the

weakness of elite politics. He, of course, opposed the act, which was

to tax several items beyond stamps – newspapers, licenses,

indentures, and playing cards. But when Franklin saw that it was to

be passed, he went along with it. He believed that the empire needed

the funding. In Philadelphia, he procured for his friend, John

Hughes, the stamp agency in Philadelphia. It almost ruined Franklin

and nearly cost Hughes' life.

Franklin

was appalled at the mobs that prevented the enforcement of the Stamp

Act – he had become out of touch with fellow colonists. The only

thing that saved Franklin's Tory reputation was his four-hour

testimony before Parliament denouncing the act in 1766. He was

beginning to doubt and resent British politics and began to feel like

a colonist once again.

The

English thought he was too colonial and Americans thought him too

English. He was, at first, caught in the middle and even tried to

calm both sides discounting plots and conspiracies from both sides.

When

in 1771, Franklin lost his chance at land scheme for settling the

trans-Appalachian West of North America, the head of that department,

Lord Hillsborough,

blocked the idea. Hillsborough even coldly refused to accept

Franklin's credentials as agent for the Massachusetts Assembly –

which stunned Franklin. It was after this failure and insult by the

English Ministry, that Franklin began to reconsider his position in

life. It was during this time he went on a series of journeys around

the British Isles, visiting a friend at his country house that he

began to write his Autobiography.

During

this period, Lord Hillsborough was fired from the ministry and Lord Dartmouth

was appointed to replace him, a friend of Franklin who invited him to

his Irish estate. This provided some optimism for Franklin in that he

might be able to better persuade imperial politicians. Franklin

stopped writing his Autobiography, which would not be completed until

1784 while in France negotiating the treaty that established American

independence.

Dartmouth,

with Franklin's help, sent several letters in an attempt to

straighten things out between England and America, but it just caused

further damage. Not being a shrewd politician, the British ministry

held Franklin responsible for the imperial crisis and was attacked

before the Privy Council in 1774 by the solicitor as being a thief

and less than a gentleman. This, of course, severed any bond Franklin

had with the Imperial British. [37]

Two

days later, Franklin was fired as deputy postmaster and he finally

came to realize that the empire and his involvement had come to an

end.

So,

in March of 1775, Franklin sailed back to America, now a passionate

American colonial patriot – even surprising John Adams, who had

always been a passionate patriot, hating the English imperial

aristocracy. Some of Franklin's passion may have been calculated in

order to convince his countrymen that he had seen the true nature of

the imperial government and society of England. Franklin had been

loyal and had been personally humiliated, more so than any other

Founder. Yet, his colleagues were surprised when Franklin showed no

mercy during the peace talks and he never forgave his son, William,

for remaining loyal to the British Crown – disowning him.

In

1776, Franklin was set to begin the history of what was to become the

United States republic. He was sent to Paris by the Continental

Congress as its diplomatic agent, the first diplomat of what would

become the United States. He spent eight years in France, and it was

the French who molded the image of Franklin that we have read about

in history books.

Initially,

France was unwilling to recognize the new nation, not anxious to war

with Britain – yet. In addition, France saw no opportunity for a

beneficial offer that supported interests of France, except severing

itself from the British umbilical cord.

Franklin

was 75 years old in 1776 and he suffered from several ailments. He

was not liked by his fellow commissioners and Americans were

suspicious of him back in the colonies. He had spent 20 years living

in London, and his son William, former royal governor of New Jersey,

was a Loyalist under arrest by the revolutionists. Still, it has been

written that Franklin was the greatest ambassador the United States

ever had by convincing Louis XVI to back the Republic while at war,

and procured several loans from a French government who was

experiencing financial difficulties, mostly from corruption of the

imperial system. It was Franklin's reputation as a scientist and

philosopher, a native genius of the backwoods of America. The French

aristocracy liked his primitive nature, his innocence and his sense

of liberty – Franklin was a literal representative of America.

Strangely, French aristocrats, like La Rochefoucauld,

became passionate about the principles of the Declaration of

Independence; even though it abolished the noble privileges they had

obtained by position and fortune. Sadly, La Rochefoucauld would later

be stoned to death by a revolutionary mob.

Franklin

was not into the powder wig fad. He dressed in a simple brown and

white linen suit and wore a fur cap and never was seen with a sword,

even at Versailles, where protocol required it for gentlemen. The

French court and nobility loved the image. They even had the idea

that Franklin was a Quaker, because he was from Pennsylvania.

Voltaire and Montaigne viewed him as a fellow philosopher, based upon

his Poor Richard literature. It was the French who invented the

Benjamin Franklin of American legend; and being so successful in

France, it was probably the happiest years of Franklin's life. In

1784 he resumed his Autobiography

and completed it.

When

the peace treaty was signed in France, Franklin was called back to

America, where he knew he would die, despite wanting to stay in

France the rest of his life.

When

he returned in 1785, he had become a national hero for his deeds in

the founding of a nation, despite not leading the revolution like

Washington, Jefferson and Adams.

When

Franklin died in 1790, a public eulogy was given by William

Smith,

Benjamin's enemy. He had been assigned the task. Washington's eulogy

was provided a hundred fold; however, it was the French that provided

the appropriate honor to the memory of Franklin.

Franklin's

public image had changed when his Autobiography

was published in 1794 and in the next thirty years, that publication

spread across the country, edition after edition.

Like

a poet, his real fame did not come until after his death.

Parson Weems

wrote in 1817 a biography of which he said about Benjamin Franklin:

O you time-wasting, brain-starving young men, who can never be at ease unless you have a cigar or a plug of tobacco in your mouths, go on with your puffing and champing – go on with your filthy smoking, and your still more filthy spitting, keeping the cleanly housewives in constant terror for their nicely waxed floors, and their shining carpets – go on I say; but remember, it was not in this way that our little Ben became the GREAT DR. FRANKLIN.

No comments:

Post a Comment

No SPAM, please. If you wish to advertise or promote website, contact me.